According to the typical Indian society, an ideal woman is the one who serves the commands set by the patriarchal society where feminity subscribes to obedience, loyalty and submission. Much of whatever we are witnessing today comes to us in the sign of tradition in nasty ways.

Yet another attempt has been made by the Karnataka High Court to redefine an Indian ideal women.

According to the court, “A woman should not fall asleep after being sexually harassed, raped or ravished, otherwise, she would cease to be an IDEAL INDIAN WOMAN.”

On 22 June Justice Krishna S. Dixit granted anticipatory bail to a rape accused and asked a few questions to the complainant as to why she went to her office at 11 pm? Why had she not objected to consume drinks (alcohol) with the accused and allowed him to stay with her till morning? The complainant explained that after the perpetration of the incident she was tired and fell asleep. Justice Dixit observed that this reaction by the complainant was unbecoming of an ‘ideal’ Indian woman.

What are the attributes of an ideal Indian woman?

This term is applied in the context of various times and cultures. For example:

- Sita, daughter of Janak and wife of Lord Rama, as the ideal Hindu or Indian woman.

- Fatimah, daughter of Muhammad and wife of Imam Ali, seen as the pinnacle of female virtues and the ideal role model for the entirety of women.

- Mary, mother of Jesus as an ideal of both virgin and mother – a concept with some pervasiveness in Latin America.

- Proverbs 31 woman: “wife of noble character”, as described in the Old Testament book of Proverbs, skilled in both household management and trade.

The above mentioned are the findings from Wikipedia.

We have plenty of publications in the market which taught a woman to be an ideal India woman. One such book is ‘Stree-Dharm Prashnottari’ by ‘Geeta Press’. The book was first written in 1926 and since then religious contractors are using it as a marker of the ‘ideal’ Indian woman.

This book is one of the most selling books by ‘Geeta Press’ and has various editions including what should be a woman’s belief, her duty, ideals of a married woman’s life, et cetera.

These adaptations of an ideal woman as portrayed in these books can be seen in various soap librettos, advertisements, news and on social media.

In 2018, human right activist, P Varavara Rao was arrested by the Pune Police. While investigating the case, the activist’s daughter K Pavana was asked humiliating questions,

“Your husband is a Dalit, so he does not follow any tradition. But you are a Brahmin, so why are you not wearing any jewellery or sindoor? Why are you not dressed like a traditional wife? Does the daughter have to be like the father too?’’, asked the police.

Recently a surprising statement was given by the Gauhati High Court on a divorce appeal. A bench of Chief Justice Ajai Lamba and Justice Soumitra Saikia claimed that if a lady has entered into marriage as per Hindu rituals and customs, her refusal to wear Shakha (conch shell bangles) and Sindoor will project her to be unmarried and/or signify her refusal to accept the marriage with her husband.

In 2017, Maneka Gandhi, former Women and Child Welfare Minister made a disgusting remark while justifying early (night) curfew for women’s hostel. She said that this is done to protect the girls from their own hormonal outbursts.

Now, even our courts have started referring to this portrayal of the ‘Ideal’ woman, while giving their judgements.

As per the Indian Bar Association (IBA) study in 2017, almost 69% of the women never complain or report sexual harassment citing a plethora of reasons ranging from fear of social stigma to a lack of confidence in the recourse system.

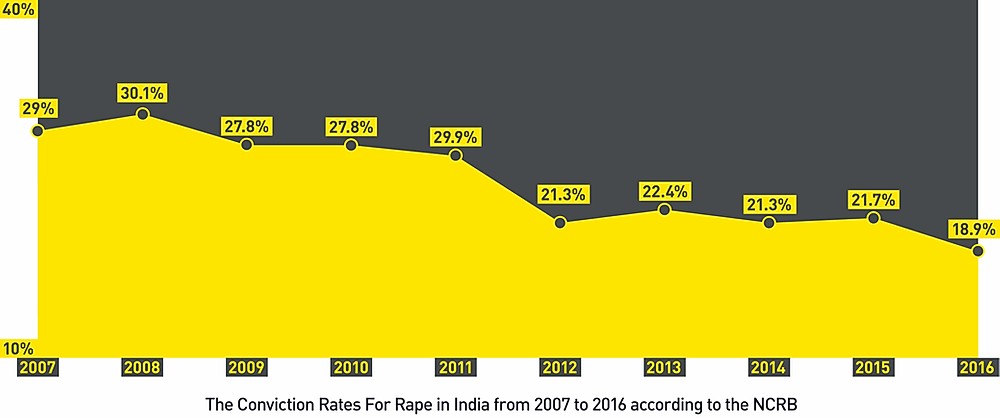

As per the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) 2018, the conviction rate in sexual harassment cases is only 18.9%.

Unfortunately, Karnataka HC’s victim shaming is not the first.

In 2018, director of film ‘Peepli Live’, Mehmood Farooqui was acquitted in a rape case after the character assassination of the complainant, an American research scholar in the court. It was said that the accused simply mistook the complainant’s ‘no’ for a ‘yes’.

Our society often makes derogatory remarks to sexually harassed women. Such as, ‘Doesn’t look like she was raped’, ‘Why is she wearing revealing clothes’, ‘Why did she leave home late at night’, ‘Why was she so friendly with her male colleague’ and many more agitating questions.

In the Karnataka rape case, the woman falling asleep after being raped is wrong because she is not married. Had she been married she could fall asleep after being sexually assaulted by her husband because marital rape is not at all considered as rape in India.

Contradictory Indian Laws

Indian laws are often incongruous with each other. For instance, in 2017, while hearing a petition, the Supreme Court said; ‘If a man has forced sexual relations with his wife who is above the age of 15, then it is no crime’. This was because of the exception clause 2 in Section 375 of IPC which stated that intercourse between a man and his wife who is not below 15 years of age, does not amount to rape.

The same law considers consensual sex between the boys and girls between the ages of 15-17 an offence.

Apart from this, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012 stated that all individuals below the age of 18 were to be considered minors.

However, in December 2017, the Court read down Exception 2 to Section 375 holding that it violated Article 14 (right to equality), 15 (non-discrimination) and 21 (right to life) of the Indian Constitution. As a result, a man who rapes his wife is now exempted only if she is not below eighteen years of age.

In 2015, the Supreme Court rejected a marital petition calling it a ‘personal issue’ and not a ‘public cause’. The petitioner alleged that she was not only subjected to dowry harassment but also brutally raped by her husband who pushed torch lights into her, causing grievous injuries.

Still, marital rape is not a criminal offence under the IPC. Marital rape victims have to take the support of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005 (PWDVA).

We must understand that an independent woman is not ‘bad’ or ‘unideal’. As we strive to empower women by initiating different governmental schemes, we must ask ourselves;

What is an ideal Indian man? What are we teaching our men? Are we preparing our men to respect an independent woman?

[zombify_post]