The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) stated last week that 2021 was one of the planet’s seven warmest years since records started. The year was roughly 1.11 °C warmer than pre-industrial levels, making it the seventh year in a row that the average global temperature changed above 1 °C.

The WMO analysis confirms two different official US evaluations issued last week, both of which predicted 2021 to be the sixth warmest year on record, tied with 2018.

Despite these cooling effects, 2021 was one of the world’s warmest years, demonstrating how powerful the long-term warming trend is. Indeed, 2021 may turn out to be the coldest year we’ve ever had. Let us reflect on the last year and what we may expect in the coming year and beyond.

According to WMO statistics, 2021 was one of the seven hottest years on record.

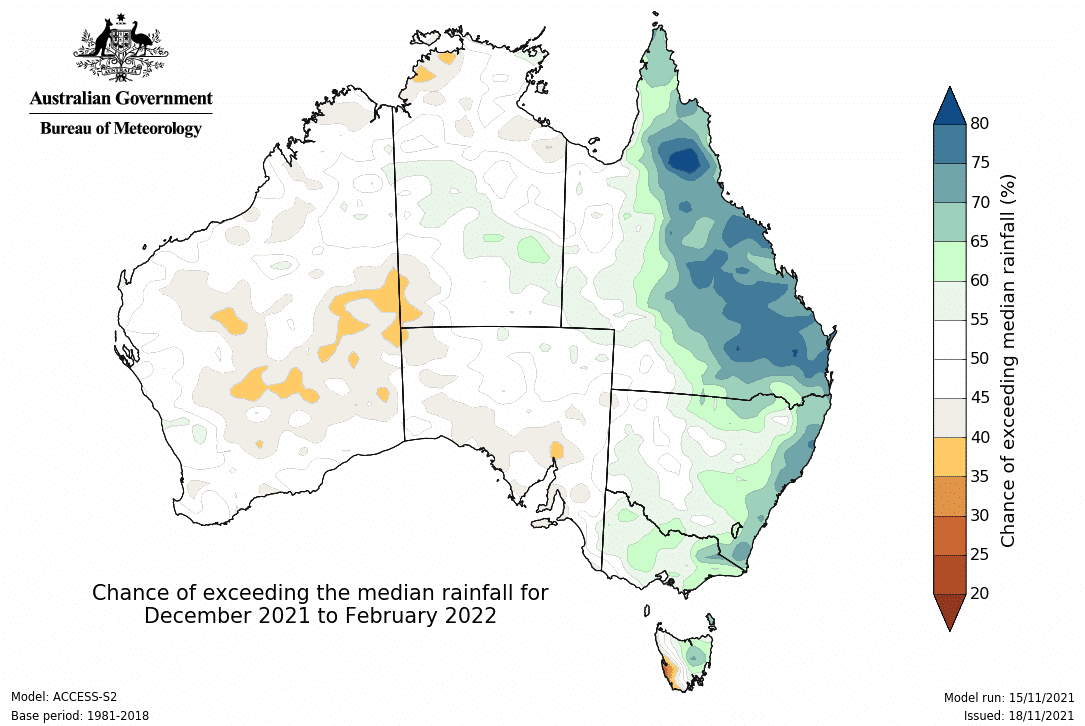

However, for many of us in Australia and throughout the world, 2021 may have seemed colder and rainier than normal. This is due to the combined influence of two La Niña episodes, a natural phenomenon that delivers colder, rainier weather to our region.

La Niña dampens the heat, but not enough

The year 2021 began and ended with the La Niña events. While this climatic event occurring two years in a row is exceptional, it is not unheard of.

During La Niña years, the world’s average temperature drops by roughly 0.1-0.2 °C. So, how exactly does it work?

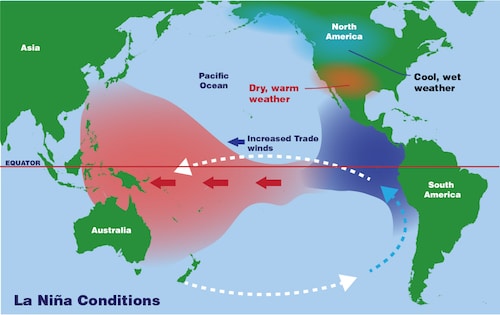

Cool water from deep in the Pacific Ocean rises to the surface during La Niña. This occurs as wind intensity near the equator increases, pushing warmer water west and allowing more chilly water to rise off the coast of South America.

The net movement of energy from the top to the deeper ocean, in essence, lowers the average world surface temperature. While La Niña is a natural occurrence created by human activity, human-driven climate change maintains a steady underlying impact that establishes a long-term warming trend.

The 2021 La Niña conditions reduced the worldwide average surface temperature. As the impacts of La Nia kicked in, temperatures in parts of Australia, Southern Africa, and northern North America were lower in 2021 than in previous years.

Unless we have another strong La Niña soon, we’ll be experiencing much hotter years than 2021 in the near future, at least until net global greenhouse gas emissions stop.

A year filled with large-scale, severe events

Extreme occurrences, particularly severe heat waves, are becoming more common as the earth heats. This was not the case in 2021, which was characterized by one very high heat event in western North America.

Heat accumulated across the northwest United States and southwest Canada in late June and early July. Several new temperature records were established around the region, some by several degrees. In Lytton, British Columbia, a stunning 49.6 °C was recorded, which is Canada’s highest temperature reading.

This heatwave was devastating, especially in Seattle and Portland, where fatality rates skyrocketed. The town of Lytton was soon devastated by wildfire.

While heatwaves occurred in many other places of the world, including large episodes in Europe and Asia, the western North American heat wave stood out. The magnitude of this catastrophe would have been nearly impossible to achieve without human-caused climate change.

Severe floods were also a hallmark of numerous regions in 2021. Because of human influence on the climate, short bursts of heavy rainfall that cause flash floods are becoming more common and powerful. In July, we witnessed particularly tragic events in Central Europe and China.

Since 2012, Australia has had its coldest year.

Australia not only suffered from back-to-back La Niña episodes but also the unfavourable Indian Ocean Dipole—akin to the Indian Ocean’s counterpart of La Niña, bringing chilly, rainy weather to the country during winter and spring.

Both had an impact, with Australia having its coldest year since 2012 and its wettest year since 2016.

Also Checkout: Positive and hopeful environmental stories that you might have missed