There have been a plethora of information, sanctions and policy-prescriptions at the government and non-government levels for the developments of tribes and carrying them into the mainstream of the population since the seven decades of our independence. They are the most expendable population in this country partaking the largest segment among the dispossessed people as we pursued ‘development’ after independence.

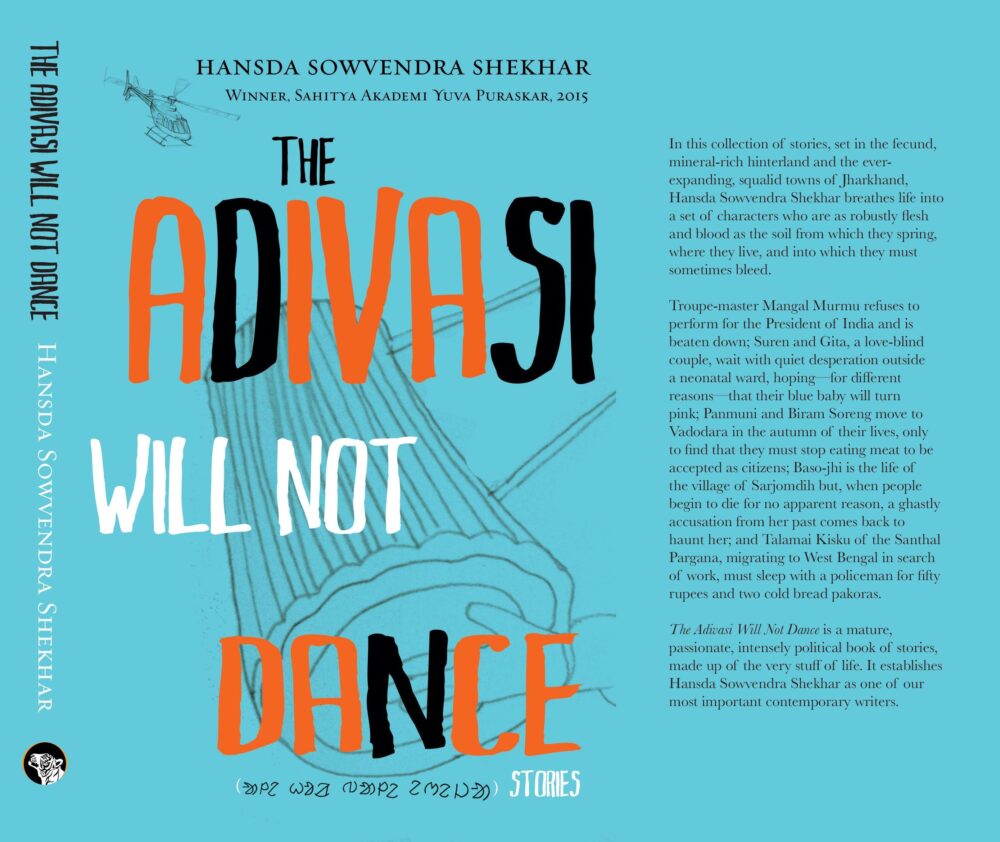

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s book, “Adivasis Will Not Dance” makes us peep into the lives of Adivasis in and from the eastern side of India, there and elsewhere. It shows us the mirror in terms of how we look at the Adivasis around us, which otherwise would take a good amount of introspection and realization. Shekhar is a Santhal – an Adivasi community belonging to Central and Eastern India – making him a unique voice in a field dominated by elite and upper-caste writers. The book is a collection of many stories revealing the different facets of life as an Adivasi in India. The pick of them being the ones mentioned below.

The book is resembling of a monologue with diminutive hope for change in the situation. It commences with an Adivasi family of four members who hail from Jharkhand’s Ghatshila and was obliged to move from Bhubaneswar to Vadodara four years earlier. Now living in a cleaner and more organized town as the renters of a South Indian landowner, they had to conceal and let go of a lot of things including their ethnicity, food habits of common non-vegetarian stuff and later on the egg-shells when they covertly began to cook eggs in their kitchen. It would instantly drag the reader towards the incidents of mob-lynching throughout the country.

The difficulties of Panmuni-jhi, the protagonist of the story, in managing up with the new food habit prescribed by the society between 2000 and 2005, is spread from Gujarat to the heart of India. The promise of a free India looks farcical today as somebody has to adhere to somebody else’s choice at the expense of their own.

One of the most heartbreaking stories of poverty and vulnerability in the collection is the third story, titled, “November is a Month of Migrations”. Symbolized through a 20-year-old girl, Talamai who is going to Bardhaman district of West Bengal with her family to plant rice and other crops in ranches owned by zamindars of Bardhaman depicts the extremes that poverty can lead to.

At the railway platform, she is approached by a young jawaan who wants to have sex with her only for “two pieces of cold bread pakora and a fifty-rupee note”. This particular short story had exasperated many readers and critics and Hansda was accused of portraying the Adivasi women in a bad light.

Out of the ten stories in the book, more than half have female protagonists or narrators at the least. While a few of these characters are defiant and daring, most of the others are weighed down by the burdens of systemic injustice and are doubly oppressed. The fact that women face injustice in very different can almost be separated in the book. And this is intended to make the reader uncomfortable and why not?

In the words of Shekhar himself- “Why must the truth be whitewashed?”

Give “The Adivasi Will Not Dance” a read if you haven’t and let us know your views in the comments section below, the book is available on Amazon. And for more such book reviews, keep checking our Iiterature section.

Also Read:

Why Does Draupadi Need Dopadi : A review of Mahasweta Devi’s “Dopadi”

8 Of The Most Expensive TV Show Episodes Ever Made