From early theatre to public speeches, to magazines, books, film, and more, propaganda pervades our society. Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines propaganda as “the spreading of ideas, information, or rumour to help or injure an institution, a cause, or a person” and as “ideas, facts, or allegations spread deliberately to further one’s cause or to damage an opposing cause, also: a public action having such an effect.”

The Literature of Propaganda examines these literary works and explores ways in which propaganda shapes public opinion, persuades its audience, and impacts society. The Literature of Propaganda showcases propaganda portrayed in literature: such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

It also features literature that was specifically created as propaganda or used in that way: such as The Moon Is Down by John Steinbeck, and The Leopard’s Spots, The Clansman, The Traitor by Thomas Dixon. Finally, it explores works that deliver a vision as described by an influential leader: such as Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler, and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung by Mao Tse-TungZedong, The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Propaganda gives a way such as the planting of information and ideas to influence and emphasize certain attitudes and behaviours. Of course, this can not be done in a short time, because it requires the process until acceptance of the concept is embedded through conditioning and habituation to the desired thing. In the propaganda, we don’t know right or wrong. The emphasis on the content of propaganda is how it is believed by someone and in turn, encourages the person to act by the objectives of propaganda.

The next is to deliver something with changing something that has good credibility so that the target receives it without knowing it. It is used as a process of mastering the dominant class to the lower class and the lower class is also actively supporting the ideas of the dominant class. Here the control is done not by force, but through consent.

For many though the propaganda has not worked. In fact, it has had the opposite effect. The need for alternative news sources is immense. The media might be failing to provide us with the information that we need but in the quest to find it a whole new generation of dissent is being galvanized by it. Besides, the media reports exactly what they were told without properly questioning it.

Propaganda in literature is just like propaganda anywhere else, except better written! Propaganda, simply put, is just rhetoric intended to manipulate the opinion of its consumers. So, any literature that is intended to influence the way you think about a subject is propaganda of a sort. Shakespeare’s Richard III is a great example of this – it portrays Richard as a terrible villain, and uses his physical deformity as an emblem of his villainy. Was Richard III actually a villain? Did he kill the twin Princes in the Tower? Probably not – but it suited the Tudors to have England believe so.

Pretty much anything you read as “literature” is propaganda in one way or another. especially if it’s part of a country’s literary canon. The literature we consider important because it upholds a master narrative typically constructed to reinforce what a country believes to be a “good” and positive representation of itself.

Take any public school textbook, you’ll find most of the atrocities committed against the indigenous population omitted, and discriminatory politics glossed over. Everything else we read and or learn is put together in a way that adheres to this narrative. The stories we tell ourselves in this way are used to create history. Which is why literary theory is such a useful tool to pick apart biases.

Scholars have determined popular literature often contains propaganda imperatives. Given the persuasive impact children’s literature has upon the reader, children’s literature containing propagandistic intent is a powerful force as it plays a crucial role in their development.

If the nineteenth century is referred to as the Age of Ideology in the History of Ideas taking into account the contributions of Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Auguste Comte, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Herbert Spencer, and Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, the present century may be called the Age of Propaganda.

The ideologies of the previous century were essentially related to the western intellectual world, whereas the propaganda of the present century is universally blessed with the extraordinary power of penetrating the barriers of language and illiteracy.

In the case of the former, the term is used to mean the effort to influence readers to share one’s attitude towards life. Taking this into consideration, Austin Warren observes that “all artists are propagandists or should be, or … all sincere, responsible artists are morally obligated to be propagandists.”

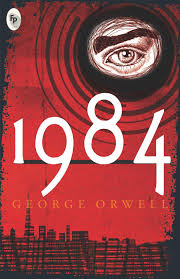

As a result of George Orwell’s passion for language and communication, both are an integral part of the novel. (He despised those who used language to falsify reality and conceal the truth.) In “1984“, Orwell expresses this frustration through the Party’s construction of their own language, known as “newspeak”. This new language was intended to supersede the existing “old speak” or English to further control the minds of its subjects.

By altering the structure of language and its vocabulary, the Party limited the ideas that the minds of individuals were capable of formulating. Ultimately, through a process of refining and perfecting “newspeak”, the Party would be able to prevent any sort of dissident or rebellious thought from being born. This would ensure absolute power for the party because no one would be able to conceptualize anything that would not fall under party doctrine.

Naturally, nothing sudden and hitherto secret is meant. The truth means the world—the only world there is. It does not change except as great books change it, and they do not so much change it as remind us of what we knew it was. Its extent cannot be apprehended without irony, and its nearness cannot be rendered without love. A great book, being both literature and propaganda, both poetry and rhetoric, will not move us to go somewhere and do something. It will simply move us—our minds, our hearts, our nerves, our souls, our persons. When it delivers a truth, it will deliver it wrapped in that spacious envelope wherein all truths lie warm together.

When it delivers an individual, it will deliver him first as a man—as a member of that class which has been the subject of our clearest thoughts, even if like things we are still prevented from thinking to the end—and only after that as the unique fellow he is; tending in his uniqueness to become a monster, and yet, by every intelligible word he speaks, recalled to the lit regions of recognition. And when it delivers an image it will supply at the same moment a perspective—the one perspective, if its author has mastered his vision, in which particulars may continue to be visible, sound interesting, and look true.

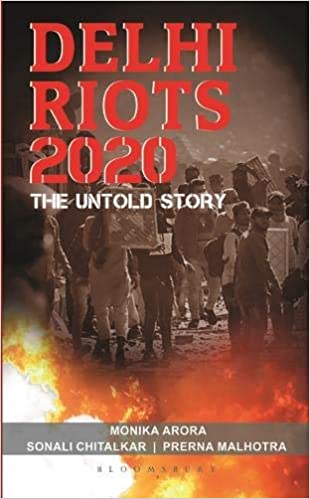

The propaganda of misinformation and hoaxes disseminated through print, graphics, and social media has altered the social landscape of this nation. It has led to multiple cases of lynching, mob violence, defamation, and riots, and continues to pose a serious threat to Indian democracy.

Recently, a controversy surrounding a book titled Delhi Riots: Conspiracy Unraveled, the 150-page book alleges that “radical” Islamic groups like Pinjra Tod, the alumni association of Jamia Millia Islamia, Popular Front of India, among others, instigated the riots in north-east Delhi by exploiting the Muslim community for their “ulterior objective of dividing the country into communal lines”.

“The reason for publishing this book on such a sensitive subject is to help in bringing the truth forward. Religious fundamentalism patronized by political parties must be exposed and this book helps to do that so we decided to take up this project,” said Prabhat Kumar, director, Prabhat Prakashan.

Owing to the massive reach of literature, it is and always has been a great source of propaganda, both political and agitative. The ideas that many times books set in our minds may be revolutionary, or even stereotypical prejudices. It has the distinguished power to change beliefs and even the truth sometimes in the process. Thus, it is us, the readers who need to decide the extent to which we let these ideas affect us, and change us.

After all, as George Bernard Shaw has said,

All great art and literature is propaganda.

– George Bernard Shaw