The story so far: Saudi Arabia, which had adopted an aggressive foreign policy in recent years seeking to expand its influence in West Asia and roll back that of Iran, its bitter rival, is now following a dramatic course correction. It’s reaching out to old rivals, holding talks with new enemies and seeking to balance between great powers, all while trying to transform its economy at home. If the Saudi drive to autonomise its foreign policy and build regional stability through diplomacy holds, it can have serious implications for West Asia.

How is Saudi foreign policy changing?

For years, the main driver of Saudi foreign policy was the kingdom’s hostility towards Iran. This has resulted in proxy conflicts across the region. For example, in Syria, Iran’s only state ally in West Asia, Saudi Arabia joined hands with its Gulf allies as well as Turkey and the West to bankroll and arm the rebellion against President Bashar al Assad. In Yemen, whose capital Sana’a was captured by the Iran-backed Shia Houthi rebels in 2014, the Saudis started a bombing campaign in March 2015, which hasn’t formally come to an end yet. One of the demands the Saudis made to Qatar when it imposed a blockade on its smaller neighbour in 2017 was to sever ties with Iran. However, the Qatar blockade came to an unsuccessful end in 2021.

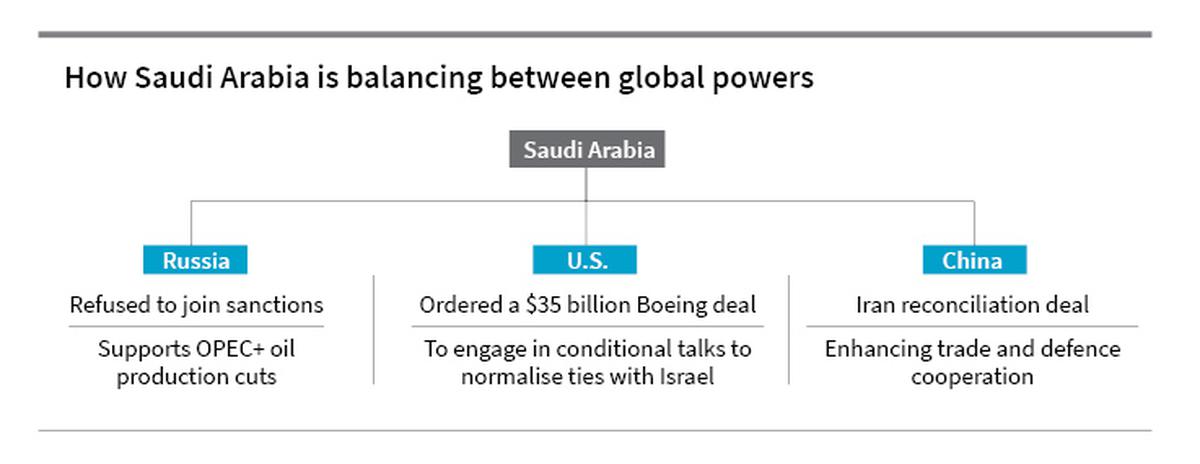

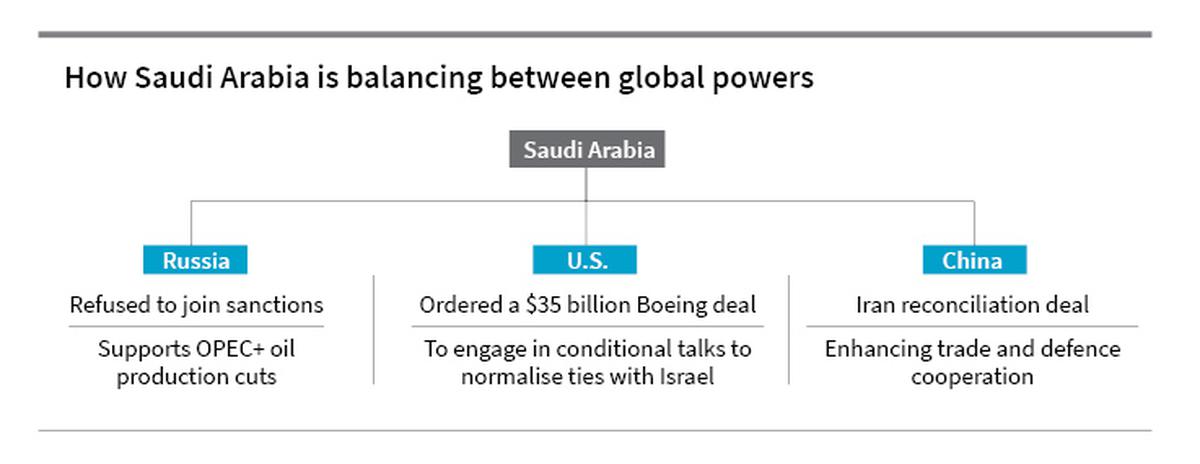

Last month, Saudi Arabia announced a deal, after China-mediated talks, to normalise diplomatic ties with Iran. Soon after, there were reports that Russia was mediating talks between Saudi Arabia and Syria, which could lead to the latter re-entering the Arab League before its next summit, scheduled for May in Saudi Arabia. Earlier this week, a Saudi-Omani delegation travelled to Yemen to hold talks with the Houthi rebels for a permanent ceasefire. All these moves mark a decisive shift from the policy adopted by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman after he rose to the top echelons of the Kingdom in 2017. Aggressiveness makes way for diplomacy and loyal alliances make room for pragmatic realignments. This is happening at a time when Saudi Arabia is also trying to balance between the U.S., its largest arms supplier, Russia, its OPEC-Plus partner, and China, the new superpower in the region.

Why are there changes now?

To begin with, these changes do not mean that the structures of Saudi Arabia’s relations with Iran are undergoing a transformation. In fact, Iran would continue to drive Saudi Arabia’s security concerns and strategic calculus. But Saudi Arabia’s response to the Iran problem has shifted from strategic rivalry and proxy conflicts to tactical de-escalation and mutual coexistence. A host of factors seem to have influenced this shift.

The Kingdom’s recent regional bets were either unsuccessful or only partially successful. In Syria, Mr. Assad, backed by Russia and Iran, has won the civil war. In Yemen, while the Saudi intervention may have helped prevent the Houthis from expanding their reach beyond Sana’a and the north, the Saudi-led coalition, which itself is now in a fractured state, failed to oust them from the capital. Also, the Houthis, with their drones and short-range missiles, now pose a serious security threat to Riyadh.

In parallel, the U.S.’s priority is shifting away from West Asia. So the choices Saudi Arabia is faced with, is to either double down on its failed bets seeking to contain Iran in a region which is no longer a priority for the U.S., the kingdom’s most important security partner, or undo the failed policies and reach out to Iran to establish a new balance between the two. When China, which has good ties with both Tehran and Riyadh, offered to mediate between the two, the Saudis found it as an opportunity and seized it.

Is Saudi Arabia moving away from the U.S.?

It is not. The U.S., which has thousands of troops and military assets in the Gulf, including its Fifth Fleet, would continue to play a major security role in the region. For Saudi Arabia, the U.S. remains its largest defence supplier. The Kingdom is also trying to develop advanced missile and drone capabilities to counter Iran’s edge in these areas with help from the U.S. and others. But at the same time, the Saudis realise that the U.S.’s deprioritisation of West Asia is altering the post-War order of the region. What Saudi Arabia is trying to do is to use the vacuum created by the U.S. policy changes to autonomise its foreign policy. The early signs of this autonomisation was visible in Saudi Arabia’s recent decisions.

Unlike most other American allies, Saudi Arabia refused to join anti-Russia sanctions. Despite protests from Washington, Saudi Arabia joined hands with Russia to effect oil production cuts twice since the Ukraine war began, aimed at keeping the prices high which would help both Moscow and Riyadh. (Saudi Arabia is currently undertaking massive infrastructure projects aimed at transforming its economy and to sustain those projects and meet its economic goals, the Kingdom needs high oil prices). It has also built stronger trade and defence ties with China, and the Iran reconciliation deal, under China’s mediation, announced Beijing’s arrival as a power broker in West Asia. At the same time, Saudi Arabia has placed orders for Boeing aircraft worth $35 billion and entered into conditional talks with the U.S. on normalising ties with Israel. De-Americanisation of West Asia is not a Saudi goal. Rather it is trying to exploit America’s weakness in the region to establish its own autonomy by building better ties with Russia and China and mending relations with regional powers without completely losing the U.S.

What are the implications for the region?

Saudi Arabia’s normalisation talks with Syria or its talks with the Houthis cannot be seen separately from the bigger picture of the Saudi-Iran rapprochement. If Syria rejoins the Arab League, it would be an official declaration of victory by Mr. Assad in the civil war and would help improve the overall relationship between Damascus and other Arab capitals. Likewise, if the Saudis end the Yemen war through a settlement with the Houthis (which would probably split Yemen), Riyadh would get a calmer border while Tehran could retain its existing influence in the Saudi backyard. Such agreements may not radically alter the security dynamics of the region but could infuse some stability across the Gulf.

But the path ahead may not be smooth. While the Saudis are trying to build cross-Gulf stability, another part of West Asia remains tumultuous — which was evident in the Israeli raid at Jerusalem’s Al Aqsa, Islam’s third holiest place of worship, last week. This triggered rocket attacks from Lebanon and Gaza and in return Israeli bombing of both territories. Israel also keeps bombing Syria with immunity. The impact of escalation of tensions between Israel and Iran on cross-Gulf stability remains to be seen.

Another challenge before Saudi Arabia is to retain the course of autonomy without irking the U.S. beyond a point. Though the U.S. publicly welcomed the Saudi-Iran rapprochement, CIA chief William Burns made an unannounced visit to Riyadh and complained to Mohammed bin Salman about being “blindsided” on the Iran deal, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal. The U.S. would also not be happy with Syria, where it once sought regime change, being re-accommodated into the West Asian mainstream. In post-War West Asia, the U.S. had been part of almost all major realignments — either through force or talks, from the Suez war to the Abraham Accords. But now, when China and Russia are mediating talks between rivals successfully and Saudi Arabia, a trusted ally, is busy building its own autonomy, the U.S., despite its huge military presence in the region, is reduced to being a spectator.

The story so far: Saudi Arabia, which had adopted an aggressive foreign policy in recent years seeking to expand its influence in West Asia and roll back that of Iran, its bitter rival, is now following a dramatic course correction. It’s reaching out to old rivals, holding talks with new enemies and seeking to balance between great powers, all while trying to transform its economy at home. If the Saudi drive to autonomise its foreign policy and build regional stability through diplomacy holds, it can have serious implications for West Asia.

How is Saudi foreign policy changing?

For years, the main driver of Saudi foreign policy was the kingdom’s hostility towards Iran. This has resulted in proxy conflicts across the region. For example, in Syria, Iran’s only state ally in West Asia, Saudi Arabia joined hands with its Gulf allies as well as Turkey and the West to bankroll and arm the rebellion against President Bashar al Assad. In Yemen, whose capital Sana’a was captured by the Iran-backed Shia Houthi rebels in 2014, the Saudis started a bombing campaign in March 2015, which hasn’t formally come to an end yet. One of the demands the Saudis made to Qatar when it imposed a blockade on its smaller neighbour in 2017 was to sever ties with Iran. However, the Qatar blockade came to an unsuccessful end in 2021.

Last month, Saudi Arabia announced a deal, after China-mediated talks, to normalise diplomatic ties with Iran. Soon after, there were reports that Russia was mediating talks between Saudi Arabia and Syria, which could lead to the latter re-entering the Arab League before its next summit, scheduled for May in Saudi Arabia. Earlier this week, a Saudi-Omani delegation travelled to Yemen to hold talks with the Houthi rebels for a permanent ceasefire. All these moves mark a decisive shift from the policy adopted by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman after he rose to the top echelons of the Kingdom in 2017. Aggressiveness makes way for diplomacy and loyal alliances make room for pragmatic realignments. This is happening at a time when Saudi Arabia is also trying to balance between the U.S., its largest arms supplier, Russia, its OPEC-Plus partner, and China, the new superpower in the region.

Why are there changes now?

To begin with, these changes do not mean that the structures of Saudi Arabia’s relations with Iran are undergoing a transformation. In fact, Iran would continue to drive Saudi Arabia’s security concerns and strategic calculus. But Saudi Arabia’s response to the Iran problem has shifted from strategic rivalry and proxy conflicts to tactical de-escalation and mutual coexistence. A host of factors seem to have influenced this shift.

The Kingdom’s recent regional bets were either unsuccessful or only partially successful. In Syria, Mr. Assad, backed by Russia and Iran, has won the civil war. In Yemen, while the Saudi intervention may have helped prevent the Houthis from expanding their reach beyond Sana’a and the north, the Saudi-led coalition, which itself is now in a fractured state, failed to oust them from the capital. Also, the Houthis, with their drones and short-range missiles, now pose a serious security threat to Riyadh.

In parallel, the U.S.’s priority is shifting away from West Asia. So the choices Saudi Arabia is faced with, is to either double down on its failed bets seeking to contain Iran in a region which is no longer a priority for the U.S., the kingdom’s most important security partner, or undo the failed policies and reach out to Iran to establish a new balance between the two. When China, which has good ties with both Tehran and Riyadh, offered to mediate between the two, the Saudis found it as an opportunity and seized it.

Is Saudi Arabia moving away from the U.S.?

It is not. The U.S., which has thousands of troops and military assets in the Gulf, including its Fifth Fleet, would continue to play a major security role in the region. For Saudi Arabia, the U.S. remains its largest defence supplier. The Kingdom is also trying to develop advanced missile and drone capabilities to counter Iran’s edge in these areas with help from the U.S. and others. But at the same time, the Saudis realise that the U.S.’s deprioritisation of West Asia is altering the post-War order of the region. What Saudi Arabia is trying to do is to use the vacuum created by the U.S. policy changes to autonomise its foreign policy. The early signs of this autonomisation was visible in Saudi Arabia’s recent decisions.

Unlike most other American allies, Saudi Arabia refused to join anti-Russia sanctions. Despite protests from Washington, Saudi Arabia joined hands with Russia to effect oil production cuts twice since the Ukraine war began, aimed at keeping the prices high which would help both Moscow and Riyadh. (Saudi Arabia is currently undertaking massive infrastructure projects aimed at transforming its economy and to sustain those projects and meet its economic goals, the Kingdom needs high oil prices). It has also built stronger trade and defence ties with China, and the Iran reconciliation deal, under China’s mediation, announced Beijing’s arrival as a power broker in West Asia. At the same time, Saudi Arabia has placed orders for Boeing aircraft worth $35 billion and entered into conditional talks with the U.S. on normalising ties with Israel. De-Americanisation of West Asia is not a Saudi goal. Rather it is trying to exploit America’s weakness in the region to establish its own autonomy by building better ties with Russia and China and mending relations with regional powers without completely losing the U.S.

What are the implications for the region?

Saudi Arabia’s normalisation talks with Syria or its talks with the Houthis cannot be seen separately from the bigger picture of the Saudi-Iran rapprochement. If Syria rejoins the Arab League, it would be an official declaration of victory by Mr. Assad in the civil war and would help improve the overall relationship between Damascus and other Arab capitals. Likewise, if the Saudis end the Yemen war through a settlement with the Houthis (which would probably split Yemen), Riyadh would get a calmer border while Tehran could retain its existing influence in the Saudi backyard. Such agreements may not radically alter the security dynamics of the region but could infuse some stability across the Gulf.

But the path ahead may not be smooth. While the Saudis are trying to build cross-Gulf stability, another part of West Asia remains tumultuous — which was evident in the Israeli raid at Jerusalem’s Al Aqsa, Islam’s third holiest place of worship, last week. This triggered rocket attacks from Lebanon and Gaza and in return Israeli bombing of both territories. Israel also keeps bombing Syria with immunity. The impact of escalation of tensions between Israel and Iran on cross-Gulf stability remains to be seen.

Another challenge before Saudi Arabia is to retain the course of autonomy without irking the U.S. beyond a point. Though the U.S. publicly welcomed the Saudi-Iran rapprochement, CIA chief William Burns made an unannounced visit to Riyadh and complained to Mohammed bin Salman about being “blindsided” on the Iran deal, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal. The U.S. would also not be happy with Syria, where it once sought regime change, being re-accommodated into the West Asian mainstream. In post-War West Asia, the U.S. had been part of almost all major realignments — either through force or talks, from the Suez war to the Abraham Accords. But now, when China and Russia are mediating talks between rivals successfully and Saudi Arabia, a trusted ally, is busy building its own autonomy, the U.S., despite its huge military presence in the region, is reduced to being a spectator.