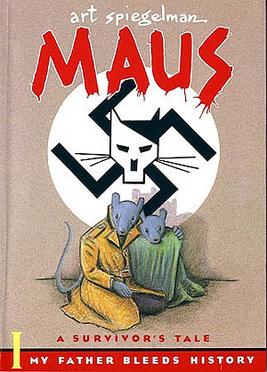

The fact that Maus is the only graphic novel ever to win the prestigious Pulitzer prize stands as monumental evidence of what an original path-breaking masterpiece Maus is. What Art Spiegelman has done in Maus(a German word meaning Mouse) is haunting, powerful, and extremely shocking; it could be termed as mandatory reading for anyone who wishes to understand the horrific Holocaust.

Any amount of critique, review, deconstruction will fall short in truly capturing the aching essence of the comic strip but one must attempt. Maus is a collection of two graphic novels with autobiographical background about the author, Art Spiegelman, and his father’s recollections about his experiences in the Second World War. Spiegelman constantly swerves between a present that’s traumatic and a past that is the origin of that trauma, between the time when he documents what his father reluctantly tells him and the time when the unimaginable events in the concentration camps took place.

Almost half of this book is actually about Art coming to terms with what his parents endured, with his issues making art about the Holocaust and making money (not to mention getting famous) off this work he feels incredibly uncomfortable about.

There was a background of depression and mental instability in his family (we learn early on that this mother was depressive and committed suicide) that their history likely exacerbated. He uses an intriguing meta-framework to approach this, highlighting conversations with his wife and therapist, to encapsulate that the experience of creating this graphic novel was a struggle on many different levels.

This harrowing portrait of the multi-generational consequences of war is probably the heart-wrenching part, for instance, this: even long after the bombs stopped dropping, the devastation thrust upon on people who weren’t even born during the war because of the unimaginable reality their parents and grandparents had to survive; it’s existential almost. Perhaps it is fitting to view it as a family memoir, although it is quite hard to classify it definitively in one category.

There is this unspoken tacit agreement in the world, in general, to treat Holocaust as a thing of remote past, almost a detached dream. Survivors and their children don’t have the safety net of forgetfulness. People can stop talking about it, they can pretend it never happened, but the recollections and imprints of these experiences don’t go away. They haunt their victims. A central and recurring theme in the book is how traumatic events like the Holocaust continue to distort and shape people generations later, long after they are over.

Progeny of Holocaust survivors are also affected by holocaust, derived and passed down through their parents. They often suffer from imposter syndrome, feeling ashamed of leading such pampered lives, compared to their parent’s horrific experiences. So, survivor’s guilt stems from first-hand experience (holocaust survivors who feel guilty for surviving when so many loved ones did not) and it percolates down through generations (children of holocaust survivors).

Vledeck’s parenting philosophy is twisted by the long-term psycho-social repercussions the holocaust has on his behavior. In turn, Art’s childhood is warped by Vledeck’s post-holocaust world view, a second-order effect of the Holocaust.

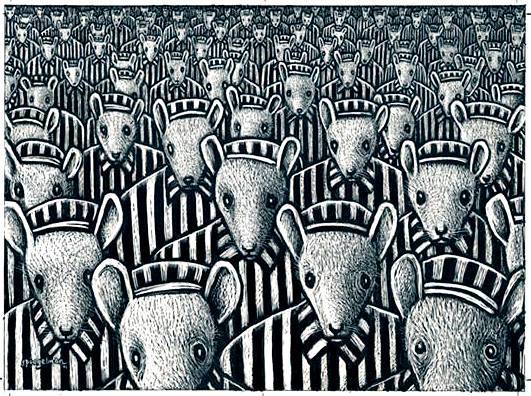

One marked tool of employing anthropomorphization of animals to depict different races and nationalities proves to be an expectantly efficacious metaphor and drives home the horror of racism. Jews are drawn as mice, which reflects back to the anti-Semitic stereotype of Jews being subhuman rats.

Germans are cats; they prey on Jewish mice. Americans are shown as dogs, they fight the German cats. The French are frogs. The Polish are shown as pigs; Nazis considered the Polish people to be pigs. Jewish Mice pretend to be Polish pigs to hide from the German Cats. They do this by wearing pigs masks. Art said in the interview that he derived the idea from old German propaganda films that depicted Jews as vermins, and that is reflective of the amount of research it went into making, almost 13 years in gestation.

The comic strips are simple, black and white, laden with texts reflecting the confused minds of the characters, while often they show Art’s interpretation of the narrative of his dad simultaneously, so you get two different accounts of the same story; how smart is that? The connoisseurs of comics often criticize Maus for simple graphics, however, one could see that Art employs minimalistic post-modern style to least distract the reader from the story, focusing on substance over style.

The book holds historical significance not only because of the subject but also because of being the first comic to attract serious academic interest, winning Pulitzer honor, while pioneering in the graphic novel industry, showing that comic strips are not limited to the fodder of superheroes, that deep dark intimate stories also offer potential, making it a seminal work worth reading.

A valuable piece of art, a strong study in interpersonal relationships and critical Holocaust literature.

Also read: