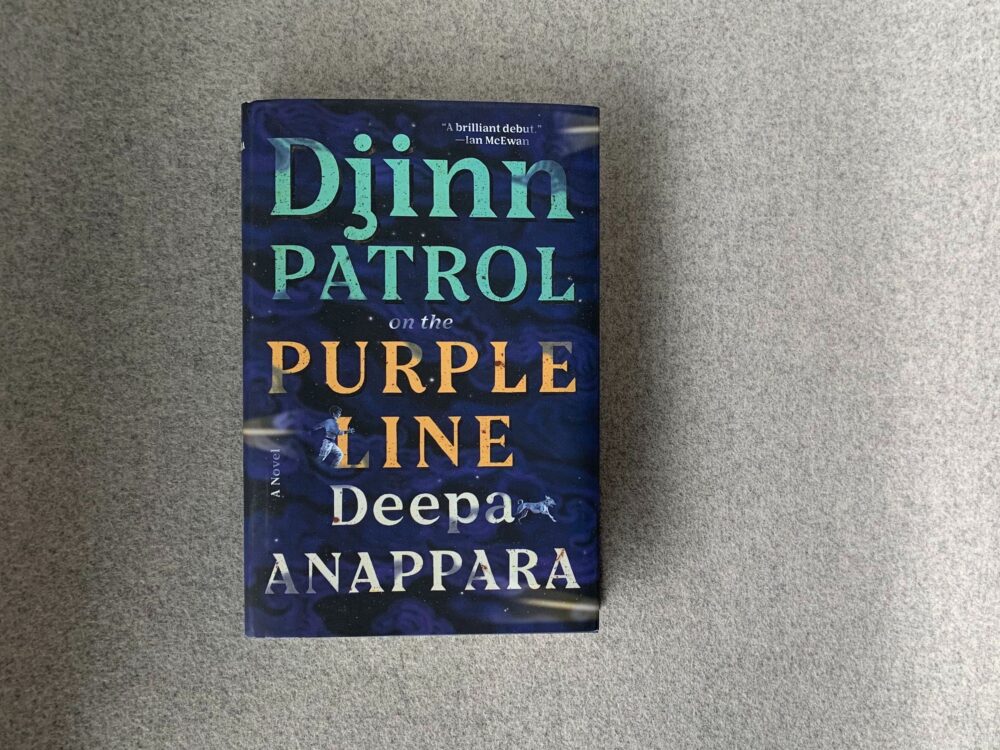

JCB Prize for Literature is an Indian literary award established in 2018. It is awarded annually with 25 lakh INR (38400 USD) prize to a distinguished work of fiction by an Indian writer working in English or translated fiction by an Indian writer. The list of the top ten nominees is now out and from the list, five titles will make it to the shortlist which will be announced on the 25th of the same month.

The winner will be announced on November 7 and will be rewarded with Rs 25 lakh prize and each of the shortlisted writers will get Rs 1 lakh each. Translators of shortlisted books will receive Rs 50,000 each while that of the winner will be awarded Rs 10 lakh. The eligible books were published between August 1, 2019, and July 31, 2020. The 2019 winner was Madhuri Vijay for her debut novel, The Far Field, set in Kashmir.

With six women writers, one woman translator, and four debut novels, there has been a prodigious change in the trends yet again. Here is a quick guide to the long-listed worth-reading nominee books.

- A Burning by Megha Majumdar

Megha Mazumdar’s debut novel is aptly named. This all-consuming story rages along, bright and scalding, illuminating three intertwined lives in contemporary India. Majumdar, who was raised in West Bengal before attending Harvard University and moving to New York, demonstrates an uncanny ability to capture the vast scope of a tumultuous society by attending to the hopes and fears of people living on the margins. It highlights the fraught relationship between politics and social media.

A train is bombed by some terrorists and people unite on social media, demanding justice. Jivan, in an impulsive post on Facebook, claims the police too are terrorists for watching so many people die. She realizes that she has made a dangerous comment, but doesn’t anticipate what awaits her. The choice of main characters in this novel viz. Jivan who is a poor Muslim woman, and Lovely, one of her believers who is from another oppressed community in India, who believes she is innocent. A Burning is a novel about the marginal, oppressed people and their inexorable fates and their fight to bring change.

- Prelude to a Riot by Annie Zaidi

Annie Zaidi’s Prelude to a Riot is a minimalist exposition of the fears and feelings of about a dozen people in a town, which is at the cusp of something very important. Set in a nameless South Indian town where upper-class Hindus have the right to carry guns without applying for individual permits, her novel looks in the eye of communal disharmony and weaponization of identity that is relevant to Indian politics today more than ever. This majority community sees the migrant plantation community, employed as cheap labor, as a threat. Prelude to a Riot has the depth of reportage and a deep understanding of the human condition. It’s like Zaidi tries to portray the events last few years and strips it down to its vulnerabilities to present to people in a form that reaches hearts directly.

- Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line by Deepa Anappara

Deepa Anappara uses a young boy’s sleuthing to illuminate the grim realities of Indian slum life in an endearing, engaging debut. This debut novel, narrated by nine-year-old Jai, meanders through a slum on the outskirts of an Indian city smothered in smog. Jai, who spends his time watching reality cop shows – until he starts working at a tea stall to earn back his mother’s savings which he has used up – observes his basti in contrast with the rich neighbourhood that lies beside it. When one of his classmates goes missing, he believes his friend has been abducted by a djinn and decides to investigate in the style of the police shows he watches. Part adventure novel and part critique of modern Indian society, this coming-of-age novel is both child-like and precociously literary.

- In Search of Heer by Manjul Bajaj

In this beautifully written novel, Bajaj primarily draws from the epic poem on Heer by the Sufi poet Waris Shah. She further adds elements from the narration of the legend of Heer and Ranjha by Damodar Gulati. To this, Bajaj adds her own imagination and her signature stylistic elements—sexual tensions and twists—to create a retelling of a popular legend that is both engrossing and stunningly subversive turning it into a transgressive feminist tale. Ranjha, the youngest of seven brothers, goes to search for Heer, his goal being to marry the famous beauty he has never even seen, revealing at the outset the face of fragile masculinity.

Heer is a feminist warrior who rides horses and demands that the sweet dishes made for her brother be shared with her. The novel is narrated by many characters, only two of which are humans – Heer and Ranjha. The others are a crow, a pigeon, a camel, and a goat. The book has all the original elements of the tragic romance: the villain, the romance, the musicality. But it successfully subverts the patriarchal notion of love, placing hope in its bleakest moments, never forgetting how community politics blends into romance. In Search of Heer is noteworthy, certainly, for the beauty of its narration, but more than anything, it is a shining example of how an author’s imagination can make a reader look at an age-old and seemingly inviolable rendition in a new way.

- Undertow by Jahnavi Barua

Jahnavi Barua’s latest novel is a coming-of-age story that resonates with our uncertain times wherein this An Assamese writer confronts migration and exile. Jahnavi Barua’s new book, Undertow, has more in common with the COVID-19 world than one might think. It is a novel about migration, exile, and loneliness, all themes we will be struggling with, in a post-pandemic world. It is the story of Rukmini, a medical student from Guwahati who marries a foreigner and is subsequently exiled from her community. Her mother Usha is the archetype of the ideal Indian woman; one who marries the man selected by her parents and dotes on her husband. Rukmini runs away to Bangalore where she still exiled from the community, constantly aware of the outsider-ness. She settles with Alex, her husband, and has a daughter, Loya who returns to Assam to find her roots and unite with her grandfather. The novel, which is centred around identity politics, becomes an important read in a time where Assam itself is experiencing political anxiety about identity.

- These Our Bodies Possessed by the Light by Dharini Bhaskar

The debut novel, These, Our Bodies, Possessed by Light, draws its title from the poem, ‘Scheherazade’, by Richard Siken. This novel is about three generations of women in Amamma, the protagonist’s grandmother, Mamma, and finally the protagonist herself. Deeya is irrevocably in love with an older man. Her mother fell in love with a man who left her. And Amamma never got to experience the love she wanted because she was married off at a young age. All three women are touched with loneliness and weave stories to protect themselves from their own heartbreak. Ultimately inspired by Richard Silken’s poem Scheherazade, the art of story-telling in this novel is reminiscent of A Thousand and One Nights. It functions at the same level as poetry: it has moments of insight about love and marriage peeking through a larger narrative of loss and grief, of myths and the telling and retelling of destinies.

- Chosen Spirits by Samit Basu

Chosen Spirits, set in a Delhi 10 years from now, is torn out of today’s headlines, and channels the anxieties that vex the Indian liberal intelligentsia. It runs on nearly untrammelled surveillance absolute compliance with government values — and an unhealthy obsession with social media influencers, called ‘Flowstars’ here. It falls into the category of dystopian science-fiction, although author Basu calls it simply “the best-case scenario.” Joey, the protagonist, is an associate reality controller. The reality of the world is bleak, where JNU is replaced by a giant mall, and Joey’s past where she attended protests at Shaheen Bagh falls into the “Years Not To Be Discussed.” Yet the book rebels against the science-fiction genre by defying the lone-male protagonist journey and converting it into the survival of the typical middle-class family in India giving it a rebellious character, but that is the job of science-fiction. Sometimes the very act of imagining a future is an act of rebellion.

- The Machine is Learning by Tanuj Solanki

In The Machine Is Learning, Solanki places his characters at the heart of the man-versus-machine debate. The book is narrated by Saransh, an MBA graduate who employs people for an insurance company that will soon be replaced by Artificial Intelligence. In fact, he is the creator of the app ISmart that will render many in his company jobless. The protagonist is aware of injustice but doesn’t do much about it. His girlfriend Jyoti pushes him to question the ethics of his work, but he has trained himself to look past it. Solanki blends technical jargon with questions about morality and weaves a narrative set in an unusual location for literary fiction in India: the corporate workplace. Through the pairing of Saransh and Jyoti, Solanki makes his characters politically and morally conscious without being swept up in waves of tokenism and armchair activism.

- A Ballad Of Remittent Fever by Ashoke Mukhopadhyay

(translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha)

This book set in Calcutta spans over some seventy years, during the British Raj, with the World War-l looming in the background, the city is riddled with plagues and infections. Dr Dwarikanath Ghoshal is an eminent physician who is observant about the rampant state of epidemics. He studied medicine against his father’s will and later converted to Christianity. Although he doesn’t completely dismiss age-old traditions and superstitions, he tries to inculcate a scientific temperament in those around him. He and three further generations of his family all work in the field of personal and public health, combating disease, viruses, and the unclean environment as well as superstition and irrational beliefs, even as their personal dramas of love, loss, and longing play out.

- Moustache by S. Hareesh

(translated from Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil)

This novel talks about the long roots of caste differences in our society through an unprecedented theme; the art of rolling the moustache, a masculine symbol of virility. The story is about Vavachan, a Dalit man who grows out his moustache, a right reserved for upper-classmen especially in the mid-20th century when this book is set, he is accused of stealing despite having no earlier record of theft. The book mixes the magic and myth of the moustache with caste politics and the rich history of Kerala giving a deep and thoughtful message at the same time.