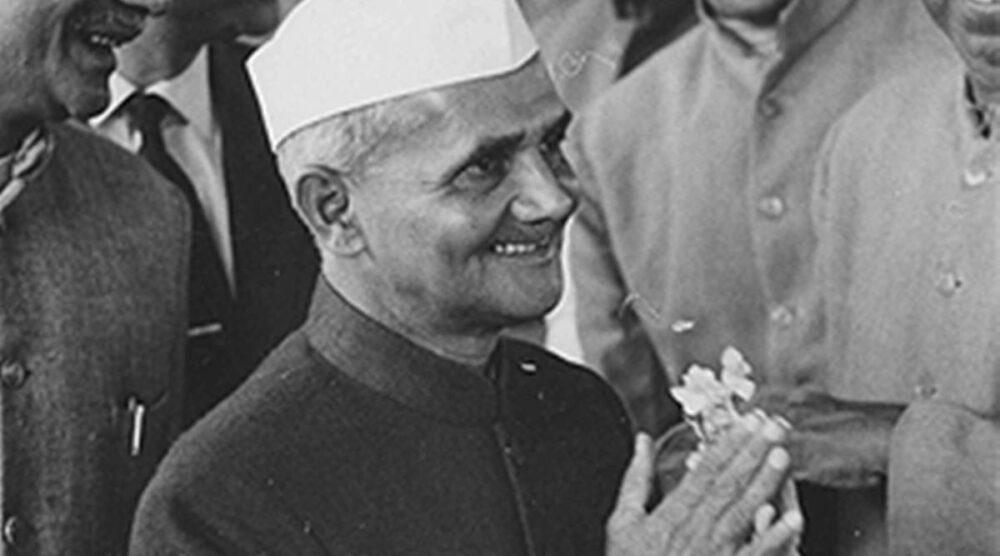

Assuming leadership of the freedom movement and enduring it for almost forty years, Lal Bahadur Shastri managed to scale atop the slimy political staircase in the well-rounded post-colonial repercussions for occupying power, facing tough contest from his antagonists. Yet, his substantial esteem is obscured into silhouettes by services at length, of his precursors and descendants.

Besides being a voracious reader of Swami Vivekananda’s discourses, Shastri was deeply influenced by Gandhi withal. Acknowledging Mahatma’s appeal to students, Shastri left school to join the Non-cooperation movement in 1920, majorly participating in anti-government demonstrations. Thereon graduating from Kashi Vidyapith, he was awarded the title ‘Shastri’ meaning scholar which by and by embellished as part of his name. He instantaneously accompanied Gandhi in the Quit India Movement of 1942, howbeit persisting imprisonment for two and a half years under charges of supporting Satyagraha.

The post-independence era welcomed Shastri as the general secretary of All India Congress Committee with Nehru as the Prime Minister. Executing a critical role in landslide victories of Congress in various forthcoming elections, he served at different positions in the cabinet, initially as the Minister of Railways and Transport in the First Cabinet of 1952, he further held office as the Minister of Commerce and Industry in 1959 and Minister of Home Affairs in 1961.

Shastri’s premiership echoes an attempt at putting things into perspective. His tenure was debatably one of the fluctuations on most fronts since it began amid a bout of food shortages and consequent price hikes. Ergo was witnessed the Food Corporation of India on the way to an eventual ‘Green Revolution’ and ‘White Revolution’ to meet food deficiencies. As a report card of Shastri in office as India’s Prime Minister, underscoring the challenges brought by recurring enforcement of Hindi that led to language violence in Tamil Nadu, perennial demand for a Punjabi “suba” and prolonged apprehension in Kashmir, were some of the challenges inflicted upon the national framework. At the diplomatic end too, Shastri had to navigate between the challenges from China, a change in the leadership of the Soviet Union while simultaneously advancing Nehru’s non-alignment policy and especially, dealing with a new leader in Pakistan, President Ayub Khan. Shastri’s culminating moment during his premiership came when he led India in the 1965 Indo-Pak War. Alleging claim to half the Kutch peninsula, the Pakistani army scuffled with Indian forces in August 1965. Nevertheless, the war ended on 23 September 1965 with a United Nations-mandated ceasefire.

Besides being a man of sensibility who toiled throughout his life for the betterment of “Harijans,” giving up his caste-derived surname of “Srivastava,” Shastri also raised the slogan of “Jai Jawan Jai Kisan” to empower the farmers and army personnel who were battling at the first line of defence during wartime. Shastri died in Tashkent, Uzbekistan (then the Soviet Union) a day after signing the peace treaty that officially put an end to Indo-Pak 1965 War, leaving a legacy to cherish for generations to come.