History and Rwanda

History is abundant with moments when morality and kindness failed.

Power corrupts men, but time has shown us that fear can be a much more vicious motivator.

It leads us to a place where all lines blur and even killing is justified. When people became their most sinister selves, we often wonder who is to blame.

Should we blame masses who were once peaceful before the carnage?

Should we blame the soldiers who swore to protect before indiscriminate destruction?

Should we blame the kings of the castle who sponsor massacres so men of power can stay in power?

After the clouds of death settle, we always want an answer to this question. We want someone to take the blame so we can move on as quickly as possible and preach hope for tomorrow standing upon the graves of the past.

History teaches us to look at Rwanda and decipher why men abandon all hope and succumb to the darkness. How fear, greed, and deceit resulted in the death of 800,000 people and how in their greatest hour of need, the world failed the souls of Rwanda.

12 May 1994

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights initiated a mission to Rwanda on 11 and 12 May 1994 to evaluate human rights violations in the country. The Special Rapporteur recommended, inter alia, an increase in the team of human rights observers in the country to facilitate the return of refugees and prevent any re-emergence of ethnic violence.

When the General Assembly adopted resolution 48/211 in December 1993, there was a flicker of hope that the armed conflict had come to an end and that Rwanda was ready to embark on a process of political reconciliation and economic and social development. These hopes were unfortunately not realized as the country once again plunged into a civil war that took the lives of as many as 500,000 Rwandans. This outbreak of violence further aggravated the already fragile socio-economic conditions in the country and led to a massive displacement of the population, requiring large-scale emergency humanitarian assistance.

To understand the 1994 genocide we have to observe it as a culmination of sub-events throughout the history of Rwanda that led to the final crises.

Rwanda consisted of three socio-ethnic groups which were mainly divisions of economic class before the pre-colonial era. 85% Hutu population indulged in agriculture while the remaining 14 % Tutsi were cattle herders and 1% Twa population worked as hunter-gatherers.

Definite distinctions between the three ethnic groups were there but lines often blurred. Gerard Prunier in his The Rwandan Crisis: History of a Genocide, pointed out that

Hutu and Tutsi lived next to each other, intermarried, and shared the same language and religion. Alain Destexhe argues that the two groups couldn’t even be described as different ethnic groups. Only during and after colonialism, the ethnic distinctions graduated into extreme racism that was evident in the 1990s. Colonizers came in and amplified the contrasts between them.

The Europeans saw the Tutsi’s long, angular features and regulated state, and considered them to be a different race from other Africans. They viewed them as superior to the “Negro race” and insisted that they had a different history. The Tutsi began to see themselves as naturally superior, the Hutu began to consider themselves as inferior. This partiality led to hostility and resentment of the Hutu toward both the European colonizers and the Tutsi.

Mahmood Mamdani examines in his book how the elite classes, the educated professionals became killers and how the origins of this hatred can be traced back to Belgian colonists who were able to turn the Hutu into the, lesser people, and the Tutsi into an exotic, Aryan race.

He argues that the Tutsi’s time in Uganda and their following incursion into Rwanda in 1990 was a critical period. It was here that the Tutsi understood that they would never be accepted as citizens in Uganda and, after the aggression when the Hutu came to believe that the Tutsi must be destroyed as a group

The Revolution of 1959 was marked by four years of nonstop attacks against the Tutsi inside of Rwanda, resulting in mass Tutsi displacement. The death of the Rwandan ruler Mutara Rudahigwa, and the succession of his pro-Tutsi half-brother signed the outset of violence between the two ethnic groups.

The Belgians were able to bring peace, and with it, replaced around half of the local Tutsi officials with Hutus. This permitted the Parmehutu, a major Hutu party, to come to succession in the 1960-61 elections. In 1961, the majority of Rwandans voted to terminate the monarchy, concluding what is now known as the Hutu Revolution.

It can be argued that, while the revolution brought in social and economic changes, it had major political obstacles. The Revolution only reinforced the ethnic divisions between the Hutu and Tutsi, polarizing the two ethnic groups to the point of no return.

The Rwandan economy

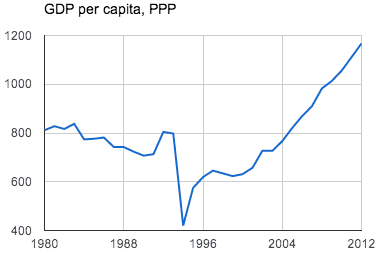

The Rwandan economy had been reasonably steady until 1986 when the coffee prices fell dramatically. As coffee was one of the country’s principal exports, an economic downturn immediately followed and continued until the outbreak of genocide.

The government accused the debt as a ‘conspiracy’ between the businessmen in the country, ‘coincidentally’ focusing on the jobs in which most Tutsi were found. To worsen the issue, Refugees in Uganda had formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front in Kampala to take control of the Rwandan government and start a military, political movement.

Founded under the leadership of Fred Gisa Rwigyema, On 1 October 1990, the RPF led by him invaded Rwanda, starting the Rwandan Civil War. This led to a movement to militarize the state money and other parts of the state. Food shortages were made worse by the fact that crucial money was being used to build up the army instead of feeding the people.

Famine was at the gates of Rwanda. Large parts of the territory seem to be entirely abandoned. Along the roads from Kigali to Byumba or to the Ugandan frontier at Kagitumba, for example, most of the villages were deserted, and the crops are not being harvested.

Fighting between RGF and RPF that broke out in October 1990, continued for almost two years until a cease-fire was negotiated in July 1992. However, it resumed in February 1993, resulting in the displacement of approximately 900,000 civilians.

The Arusha Talks

The Arusha talks, which were assisted by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and facilitated by the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania, resolved successfully with the signing on 4 August 1993 of a peace agreement that called for the establishment of a transitional government, to be replaced by a democratically elected government 22 months later.

With the prospect of peace, approximately 600,000 displaced people returned home. While some 300,000 people who remained displaced continued to rely on emergency assistance in the camps, the focus of assistance began to shift from humanitarian to rehabilitation and reconstruction.

To support the implementation of the Arusha Peace Agreement, the two parties requested the deployment of a neutral international force in Rwanda. Following the adoption of Security Council resolution 872 (1993) on 5 October 1993, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) was established and subsequently deployed.

The situation was looking optimistic and the international community with support from other United Nations agencies started to prepare for a round table on humanitarian help and restoration to solicit donor support and gather funds.

Political obstacles impeded the progress and formation of a transitional government. The round table that was supposed to happen, didn’t and the implementation of the Arusha Agreement got delayed.

Also read: Understanding the reckoning of Rwanda Part 2

Also read: WORLD DAY OF WAR ORPHANS