The Indus Valley Civilization is perhaps the earliest known urban settlement in the Indian Subcontinent. Emerging on the banks of river Indus, the civilisation has provided a great deal of historical health to us.

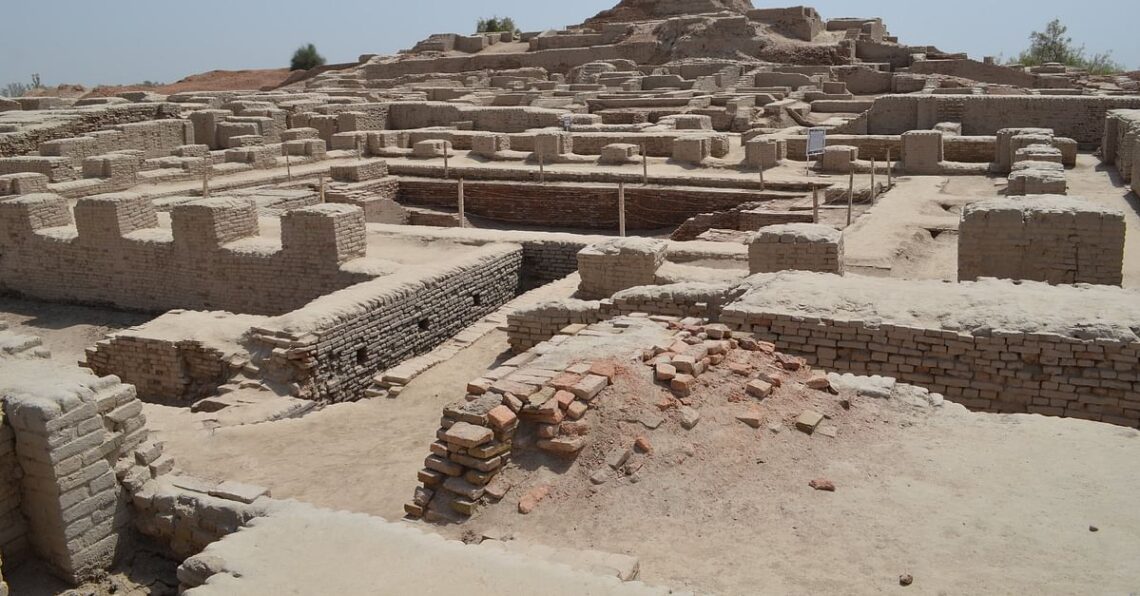

It was Sir John Marshall (during the British rule) who is regarded to set India 2000-3000 years older than it was thought to be. It is best known for its city of Mohenjodaro, which is much more well preserved than Harappa (due to brick robberies it has deteriorated).

Certain significant features that catch our eye include the drainage system, the grid pattern, and the infamous presumed ritual site, the Great Bath.

However, it hasn’t been an easy task for archaeologists and historians to reconstruct the past. Errors in interpretation can often give misleading information especially when it comes to understanding social life. The most reliable source is the written form.

Unfortunately, the enigmatic script of Harappan culture hasn’t been deciphered yet which explains the confusion that goes around as to what exactly was the language people spoke, ideas they held, etc.

Deciphering scripts broadens the horizons and enables more closed doors to open. For instance, when James Princep deciphered Kharosthi and Brahmi, many of the ancient Indian texts were finally understood right.

Now, who are the Dravidians, and why are they linked to the Indus Valley Civilisation?

The Dravidians are an ethnolinguistic group that originated in South Asia with a majority of speakers in South India. Their origin is considered very complex and open to debate.

The most common Dravidian languages are namely Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, Brahui, Coorg, Tulu, and Gondi. While it is dominantly spoken in parts of South India, it is believed to be widespread during and before Indo-Aryan migration.

The Proto-Dravidian language has no records. Though many historians have been increasingly connecting it with the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Krishnamurti says Proto-Dravidian may have been spoken in the Indus civilization, suggesting a “tentative date of Proto-Dravidian around the early part of the third millennium.”

Findings such as the late Neolithic stone celt with markings of Indus symbols and signs have been regarded as crucial evidence in tracing the connection.

Henry Heras and Yuri Knorozov worked towards surmising the symbols. Yuri, on the basis of computer analysis, said that Dravidian is the “most likely candidate” for the underlying language.

Parpola and his Finnish team investigated and agreed with most of the material produced by Heras and Knorozov and also equated Dravidian words such as ‘min’ with the symbol of fish but disagreed on certain readings.

The very recent study, published in Nature suggests that a large number of people spoke ancestral Dravidian languages. Words used for elephant such as ‘pīri’, ‘pīru’ in Mesopotamia, in Hurrian, and in Old Persian records all are taken from

the proto-Dravidian word for elephant. The research provides us with the idea that since ‘tooth’ ( pīlu) was a borrowable part of the conserved vocabulary, it indicates the possibility of Harappans speaking Dravidian languages.

Not to ignore the disclaimer put by researcher Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay that it will be wrong to assume only one language was spoken throughout the settlement.

Additionally, she said, “during the Indus Valley civilisation era, this region could have been even more multilingual, with some languages that are now extinct.”

Towards the end, the mystery of language of the Harappan Civilisation still remains unsolved but it is definitely fascinating to know that there once was a civilisation dating back to c. 3300 – c. 1300 BCE, which doesn’t fail to mesmerise us as more and more things come to light.

Also Read: 10 travel destinations in India to add to your bucket list