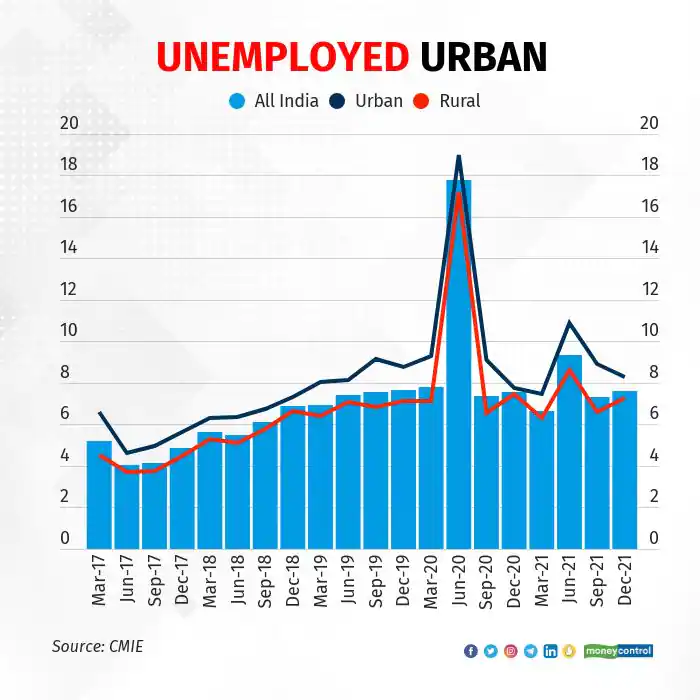

The problem of job generation in India is becoming more serious: an increasing number of individuals are no longer seeking employment.

Frustrated by the inability to find suitable work, millions of Indians, particularly women, are dropping out of the labor field completely, according to new statistics from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt, a Mumbai-based private research agency.

With India relying on youthful people to drive growth in one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, the latest figures are gloomy. Between 2017 and 2022, the total workforce participation rate fell from 46% to 40%. The picture is considerably starker among women. Around 21 million people left the labor force, leaving only 9% of the eligible population employed or searching for employment.

The issues that India faces in terms of employee development are well recognized. With almost two-thirds of the population, aged 15 to 64, competition for anything other than menial work is severe. Stable government jobs often attract millions of applicants, while admission to elite engineering schools is almost a crapshoot.

Despite Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s emphasis on jobs, urging India to strive for “Amrit Kaal,” or a golden period of prosperity, his administration has made only minimal headway in addressing the unsolvable demographic equation. According to a 2020 McKinsey Global Institute research, India needs to produce at least 90 million additional non-farm employees by 2030 to keep up with a growing young population. This would necessitate yearly GDP growth of 8% to 8.5 percent.

Failure to employ young people might drive India off the path of becoming a developed country.

Despite significant progress in liberalizing its economy, attracting the likes of Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc, India’s reliance ratio will begin to rise shortly. Economists are concerned that the country may miss out on the demographic dividend. In other words, Indians may become older, but they will not get richer.

The epidemic was preceded by a reduction in labor. The economy sputtered in 2016 when the government outlawed most currency notes in an attempt to root out illicit money. Another obstacle was the implementation of a countrywide sales tax about the same period. India has struggled to adjust to the shift from an informal to a formal economy.

The reasons for the decline in labor-force participation differ. Unemployed Indians are frequently students or stay-at-home mothers. Many of them rely on rental income, pensions from older family members, or government payments to make ends meet. Others are just lagging in terms of having marketable skill sets in a time of fast technological change.

For women, the reasons might sometimes be related to safety or time-consuming domestic obligations. Despite accounting for 49 percent of India’s population, women produce only 18 percent of its economic production or roughly half the worldwide average.

The government has made efforts to address the issue, including proposals to raise the minimum marriage age for women to 21 years. According to a recent State Bank of India analysis, this might increase labor participation by allowing women to pursue higher education and a profession.

Changing cultural assumptions may be the most difficult component.

Thakur began working as a mehndi artist after graduating from college, earning around 20,000 rupees ($260) each month painting henna on the hands of guests at a five-star hotel in the city of Agra.

Her parents, however, requested her to leave this year due to her late working hours. They intend to marry her off today. She claims that a life of financial freedom is slipping away from her.

Also, Checkout: Increase in Communal Riots: BJP’s Action and Inaction